Hearing the term “fear of missing out” or “FOMO” gives me no reason to fear. It sounds like a term invented to encourage you to “keep up with the Joneses” by tying that impulse to your quality of life, turning it into something too dangerous to get involved with. “FOMO” was first observed as a phenomenon by a marketing strategist, Dr Dan Herman, in 1996, reinforcing this thought for me.

I may have also dealt so often in nostalgia that I believe it is possible to return to everything. There is no fear of missing out on something because there is no way you can miss out, unless you limit its availability. This may be the result of the “Disney vault”, where The Walt Disney Company limited VHS releases of their classic films to keep them special and scarce, until DVD, Blu-ray and streaming video made this practice obsolete.

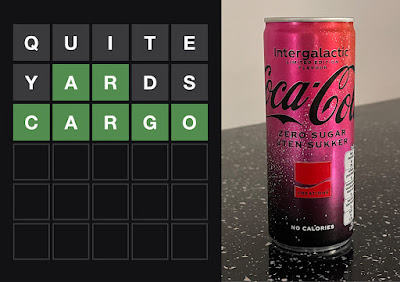

I thought the limited-edition Coca-Cola Intergalactic flavour, the first in a series of “Coca-Cola Creations”, was only to have been available in North America, but coming across it in my local supermarket was enough for me to try it. The Coke website stated that “we will collaborate to create new flavours, designs and experiences with Coca‑Cola, reimagining our iconic product in time-limited edition flavours which take inspiration from relevant moments across culture, music and gaming”. In this case, Coca-Cola was the first soft drink launched into space, on the Space Shuttle Challenger on 12th July 1985, the day after the Coca-Cola Company announced they were returning from New Coke to the classic formula.

Starting with Coca-Cola Zero Sugar, Intergalactic turned its dark caramel colour to red, its ingredients including carrot and blackcurrant from concentrates, while the taste is much like the existing vanilla Coke, with a slightly chocolate aftertaste, at least to me. It tasted fine, but not to dissimilar to a Coke flavour I can continue to drink after Intergalactic is withdrawn.

Meanwhile, I have only just started playing Wordle, a daily online word game so successful upon its launch in 2021 that it was bought by “The New York Times” for a substantial sum. Up to now, I had only seen the yellow and green grids posted on Twitter by other players, showing how well they did in guessing what letters made up that day’s five-letter word, and where that letter was placed, although the abstract nature of just seeing the letter-less grid meant it took until an idle moment on approximately day 290 of the game’s history for me to even think of trying the game. I have since concluded the first of my six attempts to guess the word should always be “quiet”, covering two vowels and the first row of my keyboard.

Wordle is a “special edition” word game in the sense that everyone is given the same word to guess in each twenty-four hour period. With no ability to go back to previous games, and with “The New York Times” issuing cease-and-desist orders on copycat websites where you can play previous days’ games, or multiple games a day, you must make a daily appointment to play, or risk missing a game on which you can never catch up. This becomes particularly frustrating if you failed to guess the word that day, or continuously failing to get the rest of a word when you got the second half fairly easily. All word games lead me to think my vocabulary is too small, so that might just be my problem.

The abbreviation “FOMO” was coined by Patrick J McGinnis in 2004, in the Harvard Business School magazine “The Harbus”, but alongside it was “FOBO”, for “fear of a better option”, the act of not making a choice because you are waiting for a better opportunity.

To me, Coca-Cola Intergalactic and Wordle are impacted by “FOBO”. One is a further dilution of the original Coke formula that had no variations until the launch of Diet Coke, but while soft drink manufacturers are fighting to hold attention, the Coca-Cola Company itself took a bolder decision by acquiring Costa Coffee in 2019 to catch where some consumers were going. While “The New York Times” may have avoided its own fear of missing out on the next big thing by buying Wordle, closing down unauthorised copies, without offering what made them so popular as an alternative to their own product, makes me think that eliminating other options for diversifying the game was needed over providing those options themselves, especially to keep the “FOMO” factor of the standard Wordle format.