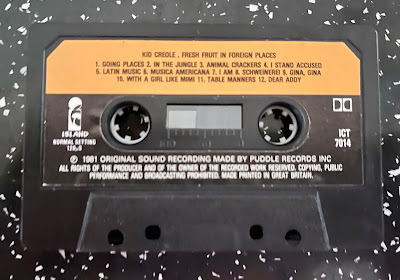

A while ago, I bought a cassette tape in a second-hand shop. It wasn’t for the album on side A, which was “Fresh Fruit in Foreign Places” by Kid Creole & The Coconuts – their most played songs, “Annie I’m Not Your Daddy” and “Stool Pigeon”, are on their following album “Tropical Gangsters” - but more about why side B of the tape was deliberately left blank.

In 1981, Island Records began a series of album releases on cassette titled “1+1”. The inlay card on my album describes it as a “revolutionary new concept… On one side there is a complete album by an Island recording artist. On the other there is a full side of blank tape. And it’s chrome tape to ensure top quality. What’s more it’ll cost you less than you would normally pay for a pre-recorded cassette. One plus one… one side what you like, one side whatever you like.” After a year, the “1+1” pattern on the packaging was minimised to a single logo at the bottom of the front cover of the cassette, which otherwise matched the regular release of the album, and would instead feature the title album in full on each side, giving you the option to record over one side. This series was discontinued in 1983, but continued in the United States by Mango Records, Island’s ska and reggae label.

However, with the marketing blurb mentioning that its cost would be lower than usually expected, I originally thought “1+1” was a novel way of packaging album re-releases. But 1981 was the year “Fresh Fruit in Foreign Places” was first released, and the “1+1” version was simultaneously released alongside the standard cassette format which, in being able to use both sides of the tape, used half the amount of tape. Meanwhile, chrome tape didn’t cost much more to buy than standard ferric tape, but its use as a selling point is more interesting today.

In 2017, I wrote that many of the advances in cassette technology, from types of tape used to Dolby noise reduction, are no longer available to new adopters of the format [link]. Buy a new blank cassette, and it will only be standard ferric tape, otherwise known as IEC Type I, which was established once new formulations of tape were created by manufacturers like BASF, that turned Philips’s original Compact Cassette from a medium for dictation into a higher fidelity format suitable for music. However, Type II chrome, Type III “ferro-chrome” and Type IV “metal” tapes, using different compounds to increase dynamic range and fidelity, haven’t been made for some time, although you now have the option of paying premium prices for the “new old stock” that remains...

...provided your cassette recorder can make use of the different tape formats. With the “Tanishin” China-manufactured cassette mechanism being effectively the last remaining cassette mechanism still being manufactured, and the only new cassette recorder I can find that still currently manufactured to record to chrome tapes, while also accounting for the maximum output levels, bias levels and time constants of different tape types, turns out to be the professional-grade Tascam 202MKVII and its TEAC-branded consumer version, costing from £400 to £600. In short, making serious use of cassettes as a recording medium in the way it used to be requires you to invest in old equipment that can take advantage of the advantages chrome tape could offer, and probably old tapes as well.

Side B of my copy of “Fresh Fruit in Foreign Places” is still blank after forty years and, unless someone buys me the Tascam unit, that is how it will have to stay.

No comments:

Post a Comment