The Atari 2600 games console was originally named the VCS, for “Video Computer System,” when it launched in 1977, and “VCS” is the name given to the neo-2600 that Atari – now probably about the fifth company to have used that name – will launch in 2019, having raised $2 million in its first day of crowdfunding and pre-orders.

The new VCS evocates the ridged black plastic and woodgrain design of the original console, except using real wood this time, while the voice-activated, Linux-based system with ARM processor is expected to play high-end PC games, along with the original 2600’s games, in addition to streaming video services.

In other words, the new VCS is a standard modern computer, but in a box designed to make you feel nostalgic for a forty-year old machine whose abilities were so limited, and so notorious for how it was programmed, it may make those that did program those games want to throw it against a wall.

Put simply, a computer will usually have a “frame buffer,” driving the display, with its own dedicated memory to store each frame before it is sent out. However, computer memory was very expensive in 1977, with the latest new home machines, like the Apple II and Commodore PET, offering only 4 kilobytes (4096 bytes) of RAM – this was also the capacity of the 2600’s game cartridges. In order to reduce the cost of the 2600 as much as possible, only 128 bytes of RAM were made available for all the variables of your game, and no frame buffer was provided at all. Making the most efficient use of the available space will also involve writing each byte in assembly language, using hexadecimal code, to be read directly by the processor.

What are you supposed to do? The answer is you have to tell the machine what to draw on each individual line of the picture you see on your TV screen. This uses only 20 bits (2.5 bytes) of the RAM each time a line is drawn, but you have to keep it going, and time your program correctly, or otherwise your picture falls apart. Furthermore, you can only draw the left-hand side of the screen, with the 2600’s Television Interface Adaptor (TIA) chip enabling you to copy or flip it to the right side. The TIA, also responsible for the sound and reading the instructions given by joysticks and paddles, also provides the two on-screen player sprites, two “missiles,” and one “ball” to make your game – when the most people have played at home is “Pong,” that really is all you needed.

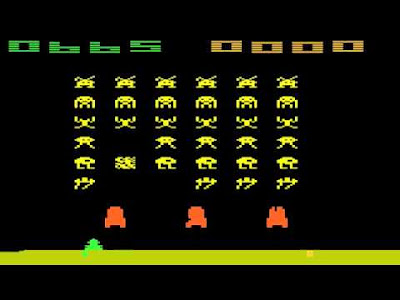

In time, people knew how to exploit the opportunities created by “racing the beam,” attempting to create more detail on screen by timing each line to draw multiples of sprites before the end of each line is reached – this means the bank of alien spaceships required for “Space Invaders” to work became possible, and the release of the most dynamic game yet for the 2600 caused sales of the system to explode. Atari’s own search for producing the best backgammon game that ran “bank switching” between different chips, allowing for bigger, more complicated games, and 1982’s “Pitfall!,” one of the most advanced games for the 2600, was created to make use of a realistic running man that programmer David Crane had made three years earlier.

The Atari 2600 was finally withdrawn from sale in 1992 – as there was no exclusive deals to produce games, and no copy protection in the cartridges, anyone could produce a game for the machine, so nobody stopped. Even now, homebrew programmers continue to see the restricted nature of the 2600 as a challenge, most notably a version of “Halo” written by Ed Fries, who led the team at Microsoft that created the first Xbox console.This is a very simplified version of how the Atari 2600 works, but when you then look up the story about the debacle over the “E.T. The Extra Terrestrial” game, it becomes clear that the programmer Howard Scott Warshaw needed longer than the five and a half weeks given to him to make something more refined.

No comments:

Post a Comment